The divergence of vision models across microns and miles reveals why the most powerful AI is the one most perfectly adapted to its physical ecosystem.

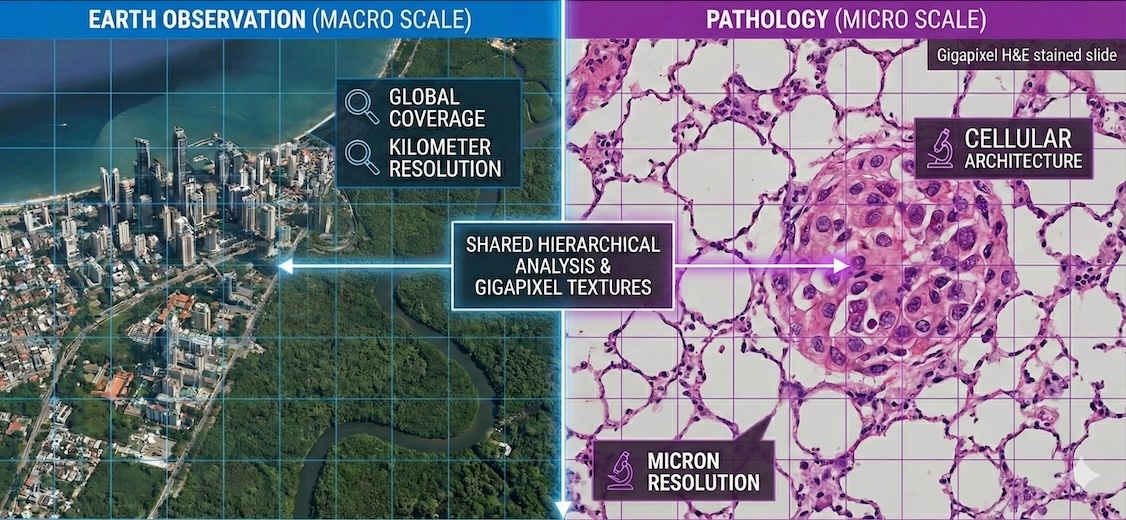

At first glance, a satellite image of the Amazon rainforest and a high-resolution scan of a breast cancer biopsy have very little in common. One captures the rhythmic, sprawling changes of our planet across kilometers; the other captures the chaotic, cellular architecture of disease across microns. Yet, in the world of AI, these two fields are currently locked in the same high-stakes race: the quest to build the definitive Foundation Model (FM) for their respective domains.

We’ve seen the GPT moment for text, where a single, massive model can handle everything from poetry to Python. A similar revolution is unfolding in computer vision. Instead of training small, specialized models for each individual task—such as identifying a specific crop type or grading a specific tumor—researchers are building Swiss Army Knife backbones that understand the language of pixels before they are ever shown a single label.

However, a strange divergence has emerged. Pathology has rapidly converged on a few massive, industry-led architectures—powerhouses like Virchow or Atlas that rely heavily on the DINOv2 recipe to create state-of-the-art feature extractors. Earth Observation (EO), by contrast, remains a wild frontier of experimental diversity. Even as industrial titans enter the arena—with Google’s AlphaEarth pushing planetary-scale embeddings and IBM’s Prithvi (in collaboration with NASA) championing masked autoencoders—no single approach has proven the best.

This isn’t just a matter of technical preference. The split between the macro and the micro reveals a deeper story about data silos, label density, and a fundamental disagreement over model design. In pathology, the goal is a monolithic, strong encoder that works out of the box. In EO, the goal is often a flexible, multimodal backbone that can be adapted to Earth’s many dimensions. By examining why these two fields have taken such different paths, we can see how AI is being built to work—whether that means a doctor using it to detect a rare cancer or a scientist using it to predict a massive flood.

The Current State: Giants and Explorers

The landscape of FMs in pathology and EO looks like two different ecosystems. One is a high-yield plantation where a few robust species have taken over; the other is a sprawling, chaotic rainforest where new forms of life emerge every season.

Pathology: The Consensus of Giants

In computational pathology, a technical consensus has rapidly formed around a specific architectural recipe: the Vision Transformer (ViT) paired with DINOv2 (a self-distillation objective). This pairing has fueled the creation of giant models that have redefined the field’s state-of-the-art.

Massive Parameter Scaling: The field has moved from early million-parameter encoders (like ResNet-50 or ViT-Base) to true heavyweights. Models such as H-Optimus-1 (Bioptimus, 1.1B parameters) and Virchow 2G (Paige, 1.85B parameters) have set a new industry standard. Most recently, the release of Atlas 2 (Aignostics/Mayo Clinic) has pushed these boundaries even further, training a 2B parameter model. This massive scaling allows models to capture subtle biological features—such as cellular organization and nuclear variation—that smaller models often overlook.

Data Diversity as the Differentiator: The focus has shifted from more data to more diverse data. Atlas 2, for instance, was trained on 5.5 million whole-slide images across 100+ staining types and multiple global institutions. This ensures the model doesn’t fail when it encounters a slide from a new lab with a different scanner or staining protocol.

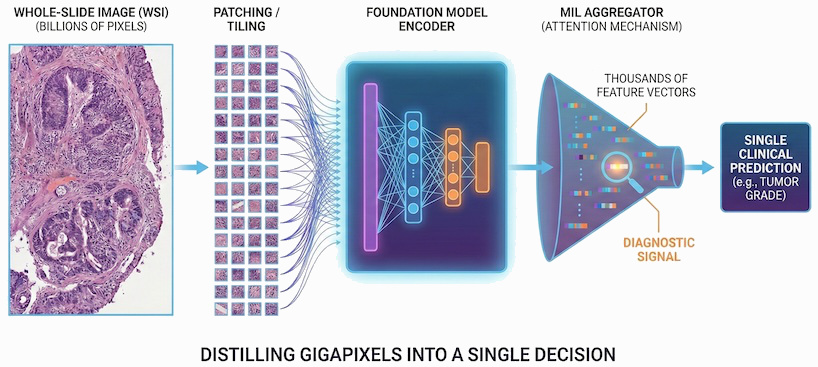

Weak Supervision: The central challenge in pathology is the needle in a haystack problem. We often have a single clinical label—such as “this patient responded to the drug”—for a gigapixel slide containing billions of pixels. Because these images are too large to process on a GPU in a single pass, they must be divided into thousands of patches. This creates a Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) bottleneck: the model must infer which specific patches contain the diagnostic signal from a single slide-level outcome. FMs solve this by acting as the ultimate feature extractors. By pre-training on billions of unlabeled patches, they create a frozen representation so biologically rich that even these sparse, weak labels are enough for the model to successfully bridge the gap between a few malignant cells and a patient’s clinical future.

The reason for this convergence is pragmatic. Pathologists primarily work with H&E-stained tissue slides, which—despite their gigapixel scale—share a remarkably consistent visual grammar. DINOv2 is exceptionally good at learning dense visual features without needing labels, creating a frozen feature extractor that works out of the box for almost any cancer type. For an industry focused on diagnostic products, this reliability is more valuable than experimental variety.

Earth Observation: The Cambrian Explosion

In contrast, EO is in the midst of an explosion of architectures. While industrial titans like Google (AlphaEarth) and IBM/NASA (Prithvi) have entered the arena, their arrival hasn’t forced a consensus. Instead, it has accelerated fragmentation.

Temporal Integration: Rather than treating images as static snapshots, newer models treat the Earth as a dynamic, shifting video. Models such as Prithvi-EO-2.0 and SatMAE use Masked Autoencoders (MAEs) to predict missing time steps, enabling the models to learn the rhythmic patterns of seasonality, agricultural cycles, and urban expansion. By reconstructing pixels over time, these models can infer what a cloud-covered field looks like from its historical trajectory, thereby turning the Earth’s surface into a temporal embedding.

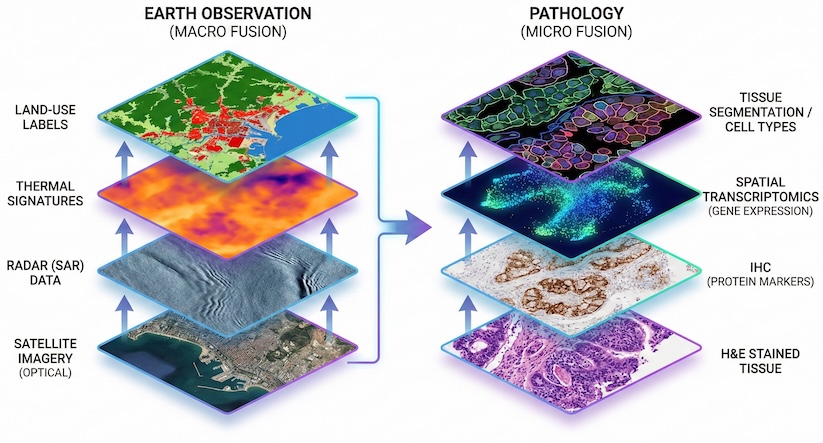

Unified Multi-Modal Backbones: Modern initiatives like Clay create a single embedding space for entirely different sensors. This involves integrating optical (RGB), thermal, multispectral, and radar (SAR) data into a cohesive representation. The goal is a model that recognizes that a heat signature from a thermal sensor and a green pixel from an optical sensor describe the same biological reality—such as a forest fire or a drought-stressed crop—regardless of which satellite is overhead.

Specialized Encoders: Unlike the one-size-fits-all approach in pathology, EO researchers often develop specialized encoders to handle the distinct physics of non-optical sensors. By using specialized encoders for SAR or Hyperspectral data, EO models can respect the unique physical constraints of each sensor rather than forcing them into a standard RGB language.

Ultimately, the EO landscape is characterized by fragmentation by design. Because the planet is a multi-dimensional, moving target, the field has rejected the idea of a single monolithic winner. Instead, big tech efforts such as AlphaEarth provide foundational planetary embeddings, while specialized academic and public-private models, such as Prithvi, serve as flexible backbones for specific tasks. This diversity is not a sign of a lack of progress but a reflection of Earth’s complexity: planetary analysis requires a diverse toolkit, not a single hammer.

Why the Divergence?

The split between the macro and the micro isn’t just a matter of technical taste; it is a direct consequence of how data is accessed, the maturity of data standardization, how data is labeled, and the institutional incentives of the groups building the models.

1. Data Access: The Open Commons vs. The Siloed Vault

The culture of the two fields is shaped by the accessibility of their primary resource, leading to a stark split between open source and proprietary ecosystems.

The EO community has built an open by default culture. Because data from programs like Sentinel and Landsat are public, most models—including Prithvi, Clay, and OlmoEarth—provide fully open code and weights. This transparency allows researchers globally to run head-to-head comparisons of different SSL (Self-Supervised Learning) objectives—like masked autoencoders versus contrastive learning—on exactly the same datasets. This open competition helps fuel the diversity of methods. Google’s AlphaEarth Foundations is the notable exception; while Google has released annual 64-dimensional satellite embeddings for public use, the actual model weights and training code remain proprietary.

In contrast, pathology data is often a siloed vault. Because the underlying images are tied to patient privacy and hospital firewalls, building an FM has an expensive barrier to entry. Because these datasets are rarely shared, it is more difficult for the community to benchmark different architectures on a level playing field. Consequently, the industry has naturally gravitated toward the most proven recipe—DINOv2—to minimize risk when working with scarce, expensive-to-access data. This has also created a landscape of closed source giants like Aignostics’ Atlas and PathAI’s PLUTO, where the model is a proprietary clinical tool. However, a hybrid open source movement has emerged: Paige’s Virchow and Bioptimus’ H-Optimus have released weights for their smaller models for non-commercial use, while keeping their most advanced versions behind commercial licenses.

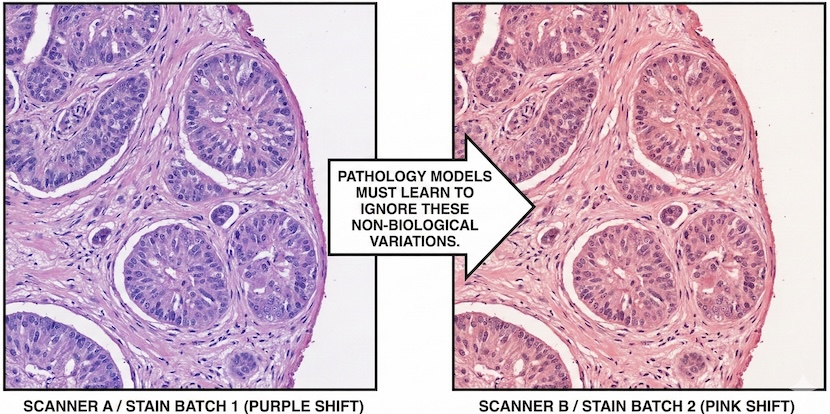

2. Data Standardization: Physical Calibration vs. Chemical Chaos

Beyond access, there is a fundamental difference in the cleanliness of the pixels themselves.

In EO, data is physically calibrated. A pixel from Sentinel-2 in 2020 is physically comparable to a pixel captured in 2024; the sensor’s physics are known and constant. This high degree of standardization allows models like MAE to focus on reconstruction because the signal is reliable.

In Pathology, there is less standardization. A purple pixel from Lab A may differ physically and chemically from a purple pixel from Lab B due to varying reagents and scanner brands. This chemical noise makes reconstruction more difficult—the model would waste capacity attempting to reconstruct artifacts from a specific lab. This encourages the move toward DINOv2, using heavy augmentation to teach the model to ignore the color and focus on the morphology.

3. Label Density: The Weak Label Bottleneck vs. Dense Prediction

The second driver is a fundamental difference in how we teach these models through labels.

In pathology, labeling individual cells is prohibitively expensive. Instead, the field relies on Multiple Instance Learning (MIL). You often have a single weak label (e.g., “this patient responded to the drug”) for a slide of 50,000 patches. Because supervision is so sparse, the model cannot readily adapt to specific biological details during fine-tuning. It requires a heavyweight, frozen encoder that is a powerful feature extractor right out of the box.

Many EO tasks, such as land cover mapping or flood detection, provide dense, pixel-level labels. When you have a label for every part of the image, the model can afford to be lighter during its initial pre-training. Researchers can use more flexible backbones because they can rely on the fine-tuning stage to steer the model toward the specific task at hand.

4. Institutional Incentives: Product vs. Publication

Finally, the who and why behind model development drive the final design.

The pathology field is dominated by startups and big pharma (e.g., Tempus, PathAI, Aignostics, Bioptimus). These organizations are under immense pressure to deliver FDA-regulated, clinical-grade products. For them, a working consensus is better than a risky breakthrough. They prioritize implementation and risk mitigation by using established architectures such as DINOv2.

While big tech is involved, the EO space is still heavily influenced by academic-public partnerships (like IBM/NASA’s Prithvi). In academia, the incentive is to innovate and ablate. Success is defined by the discovery of a better way to address the physics of spectral data or temporal changes, thereby enabling a wider variety of specialized experimental setups.

What the Macro and Micro Can Teach Each Other

Despite their divergent paths, both fields are hitting a ceiling where the other’s strategies might offer some solutions. The future of biological and planetary AI likely lies in a synthesis of these two philosophies.

What Earth Observation Can Learn from Pathology

The Power of Massive Scaling: Pathology has demonstrated that truly massive, unified backbones (exceeding 2B parameters) achieve a level of zero-shot capability that smaller models lack. While early EO models often focused on regional data—such as the United States or Europe—pathology has proven that data diversity is the true engine of robustness. EO can benefit from adopting larger, global-scale encoders that can identify rare disaster types or ecological shifts in unfamiliar geographic regions without task-specific fine-tuning.

Building for Universal Robustness: In pathology, a model is clinical-grade only if it can ignore the noise of different hospital scanners and staining protocols. The field doesn’t just hope for consistency; it actively simulates these variations as augmentations during training. EO faces a similar challenge due to variations in atmospheric conditions, solar angles, and sensor specifications across satellite constellations. EO could adopt the pathology mindset: identifying inherent variations in imagery and simulating them to build a model that remains more stable.

What Pathology Can Learn from Earth Observation

Advanced Multi-Modal Fusion: EO is the gold standard for blending sensor-diverse data, such as optical imagery, radar, and thermal bands. Pathology is entering its own multimodal era, in which a single H&E slide is no longer the sole data point. By adapting EO’s multi-sensor SSL techniques, pathology can integrate H&E stains, immunohistochemistry, spatial transcriptomics, and genomics into a single cohesive embedding space. Early research in this area is promising, but the real breakthrough may lie in applying EO’s multi-sensor logic to turn messy biological layers into a clean, actionable data stack.

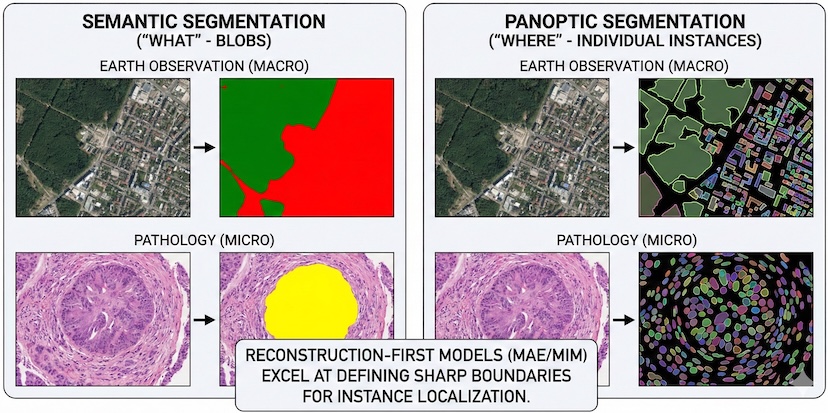

Multi-Resolution Logic: Satellite models excel at understanding the same object (a piece of land) at different spatial resolutions. Pathology can apply this logic by integrating low-resolution whole-slide overviews with high-resolution cellular zoom-ins.

Reconstruction-First Segmentation: While pathology models traditionally prioritize semantic identity (the “what”) through joint-embeddings, EO has long mastered dense localization (the “where”) through pixel-level segmentation. Reconstruction-first objectives, such as Masked Image Modeling (MIM), are inherently superior for recovering spatial detail. Unlike pure alignment models, which often suffer from semantic blur, reconstruction forces the network to learn fine-grained geometric boundaries. By adopting this EO-inspired insight, pathology models can improve pixel-level precision.

The Crucial Tradeoff: Reconstruction vs. Joint-Embedding

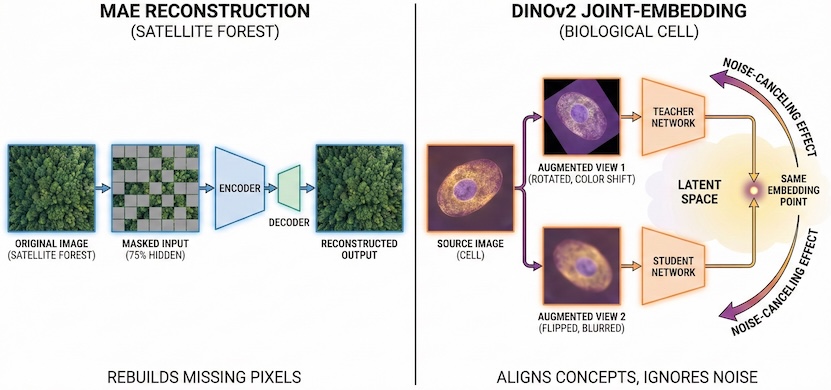

The technical divergence between EO and pathology is best explained by a fundamental tradeoff between signal reconstruction and feature alignment. While modern models such as DINOv2 have begun to incorporate reconstruction tasks (e.g., Masked Image Modeling), their primary strength is as a joint-embedding framework. To understand this, we have to look at the two different ways that FMs learn from unlabeled pixels.

The Two Philosophies

The Reconstruction Paradigm (MAE/MIM): This approach follows the logicthat if I can reconstruct the missing parts of an image, I must understand its content. Masked autoencoders hide the majority of an image and require the model to predict the missing pixels. This is highly efficient for learning fine-grained geometry and structural relationships, making it ideal for clean, physically calibrated satellite data.

The Joint-Embedding Paradigm (DINOv2): This approach follows a different logic that focuses on the underlying concepts. The model examines two versions of the same image, each distorted by strong augmentation, and learns to map them to the same mathematical representation. DINOv2 is a hybrid model that uses reconstruction to learn a cell’s shape and employs embedding alignment to determine which features are informative and which are noise.

The Role of Augmentation as a Noise Filter

In a joint-embedding paradigm, the model does not attempt to rebuild pixels perfectly. Instead, it uses two views of the same image, each distorted by augmentation, and learns to recognize that they represent the same underlying biology.

Pathology researchers have transformed this into a science through the use of simulated augmentation. By artificially varying stain colors, simulating scanner artifacts, and adjusting lighting during training, they teach the model that these variations are noise to ignore. This is why DINOv2-based models are so robust: they use reconstruction to learn the structure of a cell, but they use the embedding alignment to decide which features—like morphology—actually matter, and which—like a specific purple hue from a certain lab—should be discarded.

The Theoretical Divergence

Recent theoretical research (Van Assel et al., 2025) highlights that the mathematical success of each method hinges on the strength of irrelevant features (noise).

The Reconstruction Paradigm: When irrelevant features are low-magnitude, reconstruction is superior. It naturally prioritizes high-variance signal components—such as the sharp edges of a building or a forest canopy—and requires less tailored data augmentation. This is why it has thrived in the relatively clean, physics-constrained environment of Sentinel-2 satellite data.

The Joint-Embedding Paradigm: When irrelevant features are strong, pure reconstruction becomes a trap. The model wastes its capacity in attempting to reconstruct the noise. Joint-embedding methods, fueled by augmentation, are far more resilient.

On datasets with high levels of noise or corruption, MAE performance can drop by as much as 25%, whereas joint-embedding models like DINOv2 remain stable, with drops of only 10–12%.

A Convergent Future

As EO moves toward noisier, high-resolution commercial imagery—where atmospheric distortion and geographic bias act much like staining artifacts in a clinical lab—it may need to adopt the pathology workflow of simulated augmentation and joint embeddings. This shift would enable an FMto look past the noise of local soil colors or regional building materials to identify the underlying semantic signal. The goal will no longer be just to rebuild pixels, but to align concepts across a globally diverse and sensor-chaotic reality.

If the pathology field moves toward a label-free and slide-free future, the data landscape could shift dramatically. Emerging technologies such as quantitative phase imaging and multiphoton microscopy offer the potential to image tissue directly, thereby bypassing the chemical variability of traditional H&E staining and the mechanical artifacts associated with glass slides. If these physics-constrained imaging methods become the standard, the data could become significantly cleaner. In such a scenario, pathology may be able to move away from the heavy overhead of noise-canceling augmentations and tap into the structural efficiency of the EO recipe, using reconstruction-based models to map the architecture of disease.

Foundation Models Mirror Scientific Reality

The evolutionary paths of pathology and EO reveal that the best FM is not necessarily the largest, but rather the one most perfectly adapted to its ecosystem. Currently, pathology is optimizing for representation strength; its reliance on large joint-embedding architectures (like DINOv2) is a necessary response to the weak label bottleneck of clinical data. Conversely, EO is optimizing for architectural flexibility, using smaller models and reconstruction methods to handle a sprawling set of multi-modal sensors and temporal data.

The diverging nature of these two fields creates a unique opportunity for cross-pollination. While it is tempting for each domain to remain in its own silo, the most significant breakthroughs will likely come from researchers who can bridge the gap between the macro and the micro. By looking beyond their immediate technical constraints, both communities can refine their approaches to data diversity, scaling, and noise management, leading to more resilient and capable models.

Ultimately, the FM is not a one-size-fits-all solution, but a mirror reflecting the unique constraints and opportunities of the field it serves. Whether mapping the shifts of a continent or the mutations of a cell, these models are the lens through which we will decode the complex systems of life and our planet.